Written by: Natalia Brown

With the rapid spread of sensational images and heart-wrenching video clips capturing the physical impacts of marine debris, many of us have been faced with the reality that plastic is the least favorable material for environmental health. Social media and digital campaigns help these stories to spread rapidly, but conflicting messages about different materials may also create unproductive online debates.

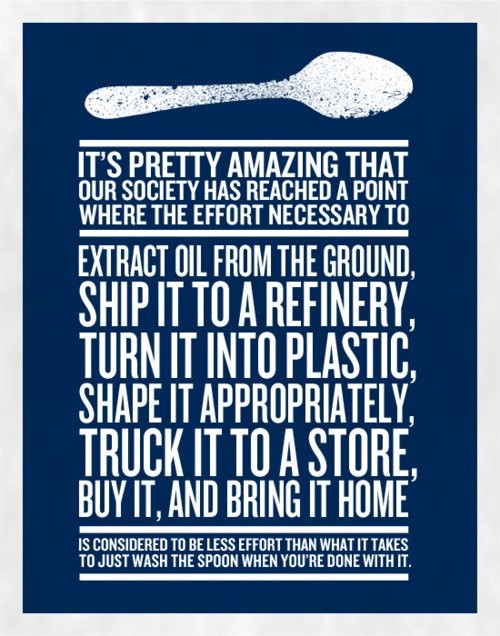

What makes this conveniently durable, widespread material more harmful than alternatives? The answer lies in the process: the life cycle of plastics.

Plastics are a category of synthetic polymers. They were designed by chemists seeking a strong, lightweight, and flexible material for consumer products. Polymers abound in nature! Cellulose, the material that makes up the cell walls of plants, is a very common natural polymer.

Synthetic, man-made polymers may be derived from natural substances like cellulose, but more often they are made using the plentiful carbon atoms in fossil fuels (such as methane gas or petroleum). These inputs allow for especially long branching to occur during polymerization chemical reactions.

Since humans learned how to create and manipulate synthetic plastics nearly 150 years ago, they’ve become a more prominent part of our lives. Most consumer products are made using some type of plastic polymer and many are surrounded by plastic packaging.

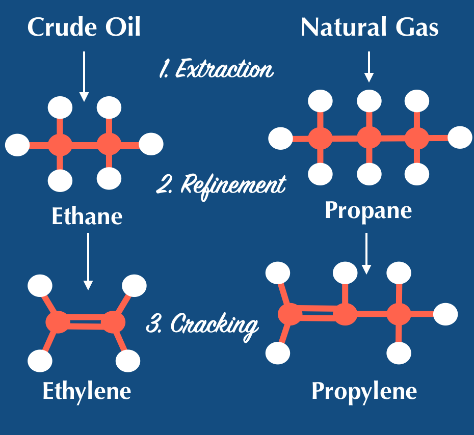

Extraction

The first step in creating a plastic product is the extraction of crude oil or methane gas. There are two main methods for these large-scale operations: mining and drilling.

Mining is used to extract solid fossil fuels by digging, scraping, or otherwise exposing buried resources. This often results in huge volumes of excess rock and soil being dumped into adjacent valleys and streams, affecting marine life and water flow. Extraction sites are also often left with poor soil and damaged land that is more prone to mudslides, landslides, flashfloods, and toxic water pollution in adjacent communities.

One Harvard University study assessed the life cycle costs and public health effects of coal from 1997 to 2005. The researchers found a link to lung, cardiovascular, and kidney diseases (such as diabetes and hypertension) and an elevated occurrence of low birth rate and pre-term births associated with surface mining practices. The total estimated cost came out to $74.6 billion every year, equivalent to 4.36 cents per kilowatt-hour of electricity produced.

Unconventional extraction methods such as natural gas hydraulic fracturing or ‘fracking’ have received a great deal of attention from advocates. Environmental effects of fracking include, but are not limited to, methane and toxic aerosol emissions, resource depletion, harmful wastewater contamination, and increased potential for oil spills and earthquakes. Importantly, all methods of fossil fuel extraction impose massive costs for fenceline communities that live, breathe, and work adjacent to these harmful industrial activities.

Refinement and Cracking

After fossil fuel extraction, the raw materials are shipped to a refinery. The goals of refinement are to derive the building blocks for plastic production: ethane from crude oil and propane from natural gas. At a cracking plant, ethane and propane are then chemically broken down into ethylene and propylene.

Processing and Manufacturing

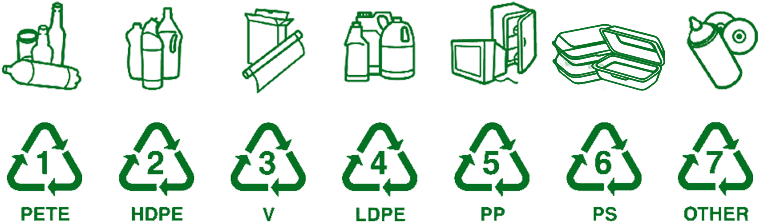

Chemical modification of ethylene and polyethylene through catalyzed polymerization produces resins. Resins are the core ingredient used to produce the durable, flexible plastics we’ve all grown dependent upon. This chemical processing can be carried out in several different ways, leading to a variety of plastic products. That’s what those numbers on the bottom of many plastic products are used to indicate!

Resins are subject to high temperature and pressue, then cooled in order to make pre-production plastic pellets called ‘nurdles.’ These plastic nurdles are the input used by manufacturers to mold and form the plastic products we use.

For example, polyethylene plastics are used to make supermarket bags and water bottles. Meanwhile, polystyrene is best known in its brittle form marketed as Styrofoam, but the same chemical building blocks are used to create toy figurines and CD cases.

Differences in the end products of plastic production are partly due to use of chemical additives that may enhance or suppress chemical properties. When mismanaged or littered plastic waste accumulates in our oceans as marine debris, plastic additives pose notable eco-toxicological risks for marine species and humans.

Distribution and Consumption

Since 1950, approximately 9.2 billion tons of plastic have been produced— 40% of which comes from single-use products such as shopping bags, cutlery, and take-out-ware. Check out this National Geographic video to learn more!

Individuals have the power to change the prominence of plastic in the consumer products industry. By changing our purchasing priorities and seeking more plastic-free alternatives, we can urge companies to embrace more environmentally-favorable materials and create more durable, reusable products.

Waste Management

Given all the resources and energy used to produce each plastic product, it’s important that we responsibly use and dispose of any plastics we already own. We can re-use, re-purpose, and up-cycle the plastics we have to make the most of their use before discarding them. This can be as simple as storing batteries in an empty take-out container or using a frayed toothbrush to clean hard to reach crevices in your coffee maker or fish tank. Get creative!

In Miami-Dade and Broward County, hard plastic narrow-neck bottles may be recycled in municipal single-stream recycling bins. Plastic grocery bags, toothbrushes, clamshell containers, and food packaging are only recyclable through third-party entities such as Terracycle or your local grocery store. They are considered contamination in your curbside recycling bin.

When plastics are separated for recycling, they are transported to a materials recovery facility for sorting. Then, they are taken to a reclaiming plant where the material is flaked, washed, and formed into new resin nurdles for manufacturing.

Recycling may be the best way to dispose of plastics that can no longer be re-used, but it is important to understand that recycling is not a long-term solution for the plastic waste crisis. Recycling is logistically challenging, energy-intensive, and can be counterproductive by reinforcing plastic consumption. Plastics are also not infinitely recyclable. Each time the material is flaked and reprocessed into nurdles, it produces a lower quality plastic that will ultimately lose its ability to be recycled.

Problems presented by the entire life cycle of plastics must best addressed by a combination of (1) increased consumer education and motivated reduction in plastic purchases and (2) regulation of plastic producers and polluters to minimize the production of plastics and harmful effects of their industrial activities.