Written by: Natalia Brown

Scientists have found tiny bits of microplastic affecting our daily activities at the biochemical level— from the household dust we inhale to the water we drink and foods we eat.

Unfortunately, it is difficult for researchers to pinpoint these important cause-and-effect relationships because we are exposed to a wide variety of different types of plastics: food packaging, clothes and linens, hygiene and personal care products, and even heavy infrastructure! Although we rely on them more than any other material, plastics and their additives remain very understudied. Most of their thousands of unique component chemicals have yet to be tested for health and safety risks.

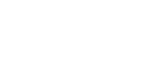

One recent study found that the average American is exposed to over 70,000 plastic particles each year! This number is only expected to grow as plastic production increases over the next couple of decades.

In this graphic, projections indicate that we’ll have produced 26 billion tons of plastic waste by 2050. Primary waste refers to plastic becoming waste for the first time. So, that value doesn’t include waste from plastic that has been recycled. [G. Grullón, Science]

You may have already seen pictures in the news and throughout social media much like this decomposing albatross with a stomach full of plastic waste.

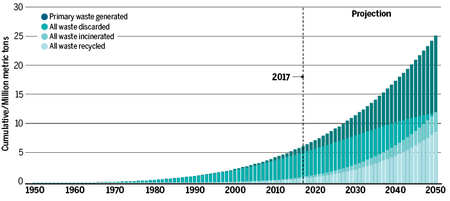

These incidents are often caused by the plastics we use and discard on land. Plastic litter is a more common problem in wealthy, industrialized countries like the US and UK. Although we have the systems and resources to manage large streams of collected waste, our access to limitless single-use products and the other conveniences have brought us out of touch with the value of the materials we discard and the immediate effects of tossing them as litter. Although our waste management systems are not flawless, following common sense standards for disposal is tremendously better than leaving trash behind in an unintended spot.

[Dan Clark, US Fish and Wildlife Service]

With the largest population, China produced the most plastic waste in 2010, nearly 60 million tons! China’s production is followed by the United States at 38 million, Germany at 14.5 million and Brazil at 12 million tons. Although this data was sourced one decade ago, distribution of waste generation has not changed much since then and is projected to look similarly into 2025.

The vast majority of trash collected from these top contributors is transported to low-and-middle-income countries through the global waste trade. Because importing countries lack the resources and infrastructure to properly manage the massive volumes of waste they receive, waste mismanagement results in coastal pollution that immediately impacts the surrounding marine life and water quality. In South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, between 80-90 percent of plastic waste exceeds the recipients’ management capacity; almost inevitably polluting nearby rivers and oceans. This source of pollution is different from the littered waste discussed as most problematic in higher-income countries because it is the result of a lack of resources and mismanagement on a larger-scale, independent of individuals’ attitudes.

No matter how they find their way into the environment, macro-plastics can be easily mistaken by marine life for food.

The jellyfish-like movement of a drifting plastic bag may come to mind, but this problem isn’t limited to physical appearances. A recent study conducted at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill found that sea turtles responded most similarly to the smell of “biofouled” plastics as to that of their own food. This finding suggests that the unavoidable accumulation of microbes, algae, plants and small animals on the surface of plastic marine debris makes it more enticing for turtles to eat our trash.

Scientists estimate that nearly all seabirds and over half of our oceans’ sea turtles have ingested plastic. This blocks their digestive tracts and diminishes their appetite, resulting in malnutrition and population decline.

Fragments of plastic bags found in a juvenile green turtle’s stomach.[Victoria Gonzalez Carman, Business Insider]

Macro-plastics cannot chemically degrade, but they do physically breakdown into microplastic bits that are difficult to see or filter out of the water. Those tiny bits contaminate our drinking water and accumulate in seafood when consumed by fish. Even more often than macro-plastics, these tiny bits of microplastics are unintentionally consumed by marine and freshwater species.

Once ingested, microplastics break down into even teenier nano-plastics that can penetrate cell membranes. This causes severe inflammation, breakage and decay of tissues in the gastrointestinal tract, absorption of harmful chemical additives, and often a stimulus response to toxicity. According to one study on the effects of nano-plastics, exposed fish exhibited severely altered feeding and shoaling behavior and metabolic function.

How does this affect human health?

Researchers from the University of California Davis and University of Hasanuddin found plastic debris in the majority of fish species sampled during their studies, all of which were marketed for human consumption. Notably, different streams of waste affected the two regions: textile fibers were found in 67% of species living off of the West coast of the US while larger microplastic debris were found in 55% of the species tested from Indonesia.

[The Ocean Cleanup]

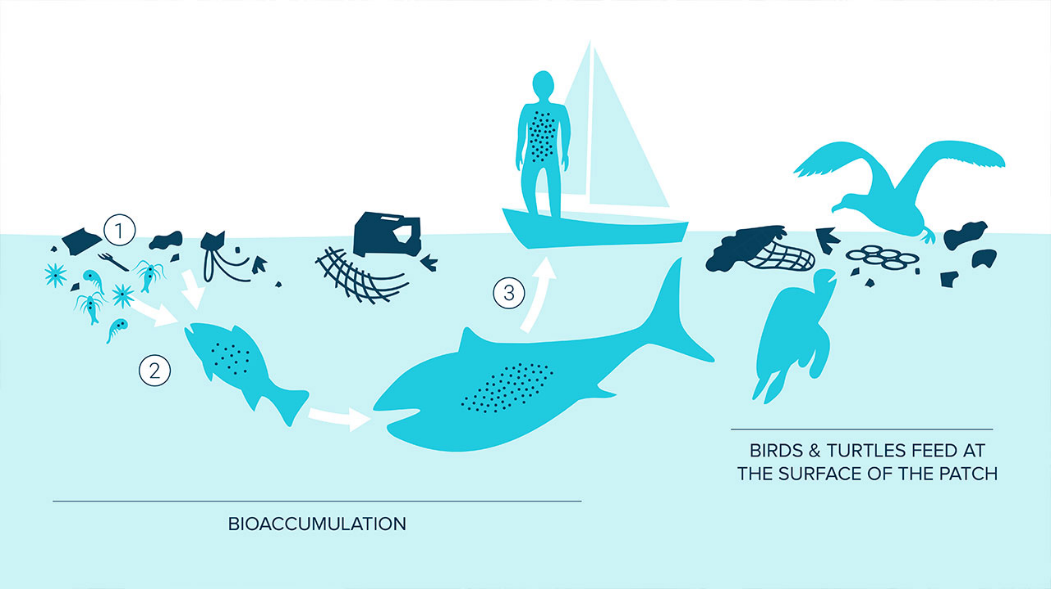

Bioaccumulation is the process in which chemicals consumed by an organism enter the food web by building up in the consumer’s tissues. In this way, the average American is said to ingest well over thirty thousand microplastic particles annually.

When plastic-exposed fish are consumed, the human body is put at an increased risk for disruption in endocrine functions related to neurological development and sexual health. The effects of some tested chemical additives have been linked to increased risk for prostate and breast cancer.

If the issue goes beyond marine species, into our drinking water and uptake by plant nutrients, how can we protect our health and address this issue over the long-term?

Survey your day-to-day activities and gradually phase out the non-essential single-use plastic products. Reducing your individual plastic consumption and opting for reusable or biodegradable alternatives will set an example for your family, friends, peers, and coworkers that’ll create a ripple effect of positive impact. When we all become stronger advocates for responsible consumption, we start to create shifts in social norms that can affect producers’ activities.

Odds are, you already have loads of plastic products at home. Don’t just throw them away! Refill, reuse, and repurpose the items you’ve already purchased or received as packaging. You will maximize utility to continue enjoying the durability of plastics while reducing your demand on new products/materials.

Advocate for responsible disposal and management of plastic waste in your home, at school, at work, at businesses you frequent, and to your local government. Spread the “trash talk” by sharing your knowledge to support a waste-conscious culture. In the United States, most of us enjoy the privilege of not seeing where the items that we throw “away” end up. That means we are all that much more responsible for learning about how we can be more proactive in reducing the waste we create and holding large polluting corporations accountable for their impacts.

Support or engage in research on the environmental and biochemical effects of plastic production, plastic consumption and use, or plastic waste. Simply sharing the results of intriguing new studies on social media can help to spread word on important findings!