Written by: Natalia Brown

We’ve all become more conscious of our surroundings throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, and many of us are starting to question behaviors we never second guessed before.

I’ve found myself clinging to my news-feed for updates on the federal relief programs and the coordination of local and state-level public health responses. That increased reliance on the media has also flooded my thoughts with alarming case projections, unproductive partisan debate, and the stories of failures to support the exacerbated needs of historically marginalized communities.

As social distancing guidelines become more stringent and stay-at-home orders are becoming more widespread, more of us are us are relying on technology to fulfill our academic and work-related obligations too. We are spending more time on our energy-intensive devices, but far less time traveling or commuting. Some people have raised intriguing questions about how these changes in out daily activities may be affecting air pollution. After all, aren’t many of the new lifestyle changes reducing our carbon footprints?

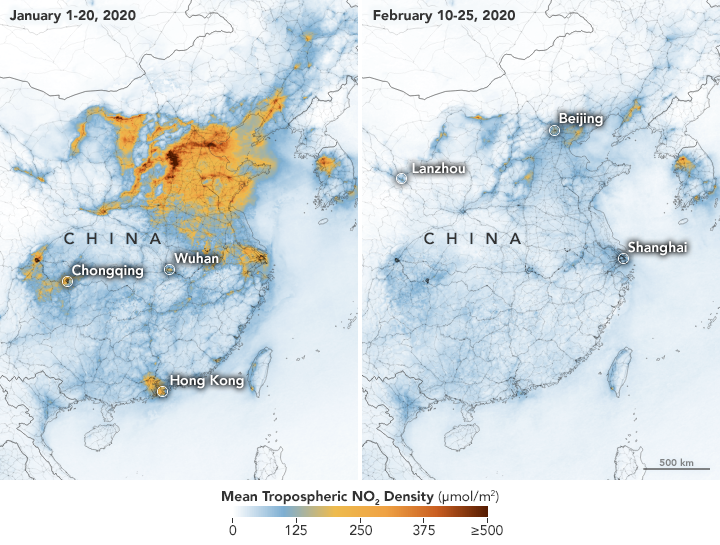

The most significant reduction in carbon emissions and air pollution has been linked to the economic slowdown, specifically reduced industrial activity and energy production as noted by LSA’s Chris Poulsen. For example, NASA and European Space Agency (ESA) pollution monitoring satellites have detected significant decreases in nitrogen dioxide (NO2) over China.

This economic downturn is not a desirable method for reducing air pollution. It is has come as the consequence of a global public health hazard that continues to take the lives of our elders, family members, dear friends, and colleagues. However, it’s worth acknowledging that recovery from this temporary slowdown can be used as a stepping stone for more environmentally favorable economic activity. Many public officials are grappling with the question of whether goals related to economic productivity, public health, and environmental protection can all be achieved simultaneously.

The COVID-19 pandemic is an excellent example of how collective action can reduce our environmental impact and mitigate severe social problems. When everyone takes action based on the evidence-based recommendations of public health experts, we collectively slow the spread of the virus and protect our communities. Similarly, as more individuals (including our elected officials and corporate elites) heed the insights of climate and biological scientists regarding the impacts of climate change and plastic pollution, we reduce the risk of exacerbating harsh impacts for frontline, coastal communities.

In spite of all lessons that we could learn from this global devastation, multinational fossil fuel corporations have driven up oil production and created a rather undesirable situation for environmental interests. The supply of oil is at a peak, meanwhile demand has collapsed due to lowed economic activity during the pandemic. This has driven the price of oil below zero for the first time in history! Global oil consumption has been in free-fall as more countries introduce unprecedented measures to fight the coronavirus outbreak. The fossil fuel industry has failed to profit from this overproduction, and they shifted their efforts from fuel refinement to ethane cracking.

Simply stated, they’re diverting the methane gas and oil that we are not consuming as fuel to produce more plastic products. Ethane cracker plants are the facilities used to process the carbon-rich inputs used to create all kinds of plastic products. Their industrial activities cause immediate health and environmental detriment to nearby communities, known as frontline or fence-line communities, while exacerbating plastic pollution impacts around the globe.

There’s more: Our team identified direct efforts by fossil fuel industry giants to ramp up demand for non-essential single-use plastics, especially plastic bags, by taking advantage of public fear and uncertainty during this time. What better time to take advantage of the public and run a manipulative campaign than a global pandemic? We are not surprised, as the fossil fuel industry has a long history of using misinformation to advance their profits at our expense. Still, this is upsetting and it’s actively misleading many concerned consumers.

The Plastics Industry Association is currently lobbying to quash plastic bag bans, even going so far as requesting that the United States Department of Health and Human Services publicly declare that banning single-use plastics during a pandemic is a health threat. Click here to read their letter.

The spread of misinformation has led many of us to question whether it’s okay to continue using reusable bags for our occasional, ultra-cautious grocery trips.

In a study cited by the Plastics Industry Association in their letter to the US DHHS, researchers at the University of Arizona and Loma Linda University found that reusable bags can contain bacteria, and users don’t wash reusable bags very often. The study was funded by the American Chemistry Council, which represents major plastics and chemicals manufacturers. Most notably: the study recommends that shoppers simply wash their reusable bags, not replace them.

There is no evidence that single-use plastics are safer than reusable items, and it’s important for all of us to recognize that single-use plastics have a number of opportunities to become contaminated during their manufacture, distribution, inventory stocking, and use. They are exposed to open air and surfaces like any other item you may be concerned about cross-contamination from. Single-use plastics could only be proven more sanitary if packaged individually in sterile conditions and handed to the customer in intact sterile packaging—much like you would imagine a syringe is packaged before use to draw blood. Clearly, that isn’t practical or realistic.

Here’s a breakdown of our options based on currently available scientific evidence:

The New England Journal of Medicine, the world’s leading medical journal for over 200 years, published data in mid-March of this year that shows SARS-CoV-2 is more stable and has a longer lifetime on plastic and stainless steel than on copper or cardboard. Viable SARS-CoV-2 was detected up to 72 hours after application on plastic, while none was measured on cardboard after 24 hours.

There is no evidence presented here to back the claim that “single-use plastics are often the safest choice” as has been pushed upon the US DHHS. In fact, the findings suggest that cardboard is a safer single-use material than plastic with respect to COVID-19 viability.

Another scientific study focused on the stability of SARS-CoV-2 in different environmental conditions showed that the virus is more stable on plastic than on printing or tissue paper, wood, cloth, glass, or banknotes. SARS-CoV-2 remained detectable on plastic for 4 days, while on paper it was not detected after 30 minutes, on wood or cloth after 1 day, and on banknotes after 2 day.

According to the Center for Disease Control, COVID-19 is most often spread directly from person-to-person. However, viral spread from contact with contaminated surfaces or objects is possible. Guidelines issued by the CDC do not make a distinction between the items this may include, so we can safely assume that their recommendations apply to single-use and reusable items equally.

Single-use items are not sterile and are bound to be exposed to microbes before reaching their end users. This means that handling a single-use plastic bag, utensil, container, or cup likely poses an equal risk of infection as any reusable item.

That said, Maine, Massachusetts, and a growing number of other states are still moving quickly to allow for delays and suspensions of plastic bag bans. In New Hampshire, the governor actually issued an emergency health order requiring stores to use single-use paper or plastic shopping bags.

We, at Debris Free Oceans, acknowledge that the nature of COVID-19 poses unusual risks. The virus may be contracted and transmitted asymptomatically, and it is understandable that reusable items such as shopping bags may be an object of concern. We urge you to make that decision based on your individual circumstances, but acknowledge that banning reusable items is an unsupported attempt that will not be a long-term solution to cross contamination.

Judith Enck, a former regional administrator for the Environmental Protection Agency, has called the plastics industry’s recent actions “shameless” and exploitative. We agree with her statement that it is understandable to use single-use materials occasionally, when necessary or beyond our control, but “in terms of overturning or delaying laws, [Enck sees] no independent data that supports that move.”

We are all struggling in some way to navigate this new normal. Pro-environmental habits, plastic waste reduction among others, may bring about a sense of normalcy and fulfillment amidst all the current uncertainty.

First and foremost, we strongly suggest that you wash all materials that may pose risks for cross contamination: reusables (bottles, bags, wash cloths) as well as commonly touched surfaces (steering wheel, door handles, cell phone, credit cards and wallet). If you find yourself under circumstances where you must resort to single-use materials, we suggest that you prioritize non-plastic alternatives in the best interest of your well-being and environmental health.

We stand in solidarity with all those who have made sacrifices to stay home, stay distanced, and protect our communities. We are privileged with the time and resources to consider reusables when so many of our neighbors, family members, friends, coworkers, and local leaders are charged with the challenges directly posed by this dangerous pathogen. Adhering to the guidance of public health professionals is the least we can do to support the courage and generosity of the healthcare workers and first responders at the frontlines of this crisis.